After all the flooding we were gradually getting back to normal at home and were doing a little maintenance about the place. The sort that requires a trip to a somewhat large, soulless barn of a hardware chainstore.

In our house, trips to this particular store are a dreaded event, so I decided to tag along with my husband to provide moral support, guidance and a hand written list so we didn’t deviate from our intended purchases.

I guess we should have expected it, because when we arrived the place was shut up having been inundated by flood waters a few days prior. So we decided to try a small local hardware store, one that we usually prefer to go to anyway but had expected would be closed this Saturday afternoon as was the owner’s normal habit.

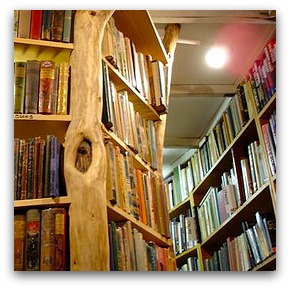

But, bless him, he was capitalising on his rival’s bad luck and in true entrepreneurial spirit was doing a roaring trade in mops, buckets and rubber gloves. I left hubbie to it and ducked into the second-hand book store next door. Much more my cup of tea! Inside, almost buried among the stacks of dusty volumes was an elderly gentleman tapping painstakingly away on his computer. He must have been late seventies or even into his eighties.

“Are you still open?” It was 4pm on a Saturday afternoon.

“Yes, but normally I would be closed by now; I just have a bit more work to do and then I am going home. But come in and take a look.”

I asked him if he had any old knitting books, particularly those from the 40s and 50s. It’s a bit of a hobby of mine hunting out old patterns. Anyway we got chatting. He didn’t have any books for me but that was OK. Then he asked me, “Are you from a big city - like London

“Why do you ask?”

“Well,” he said, “you talk very quickly and I thought you must come from somewhere like that”.

I had heard that people from cities talked faster; and that they also required smaller personal spaces (the area immediately around a person that they regard psychologically as being their own): both traits arising from the fact they were used to being jammed into crowded spaces and having to talk quickly to get their message across in a tight time frame where everyone is so harried and hurried.

Funny really. I never thought of myself as being a fast talker at all. I had always assumed I came across in reasonably measured tones. Maybe we talk faster when it is something we are passionate about?

Anyway, I was out walking this morning and thinking, as one does, contemplating the world at large, and this man’s question about where I hailed from came back to me and it made me think about two friends of mine and how they communicated.

One is a woman from New York

Cindy is at the prestissimo end of verbal communication: she leaves allegro for dead.

Cindy, trained as a barrister, has so obviously come from a fast-paced city environment. Her words are clearly enunciated, you can follow every one, but you are left feeling out of breath as you watch her, fascinated by the momentum she accomplishes.

Then there is my other friend. We’ll call him Stan. Stan hails from Norfolk Island , a small remote dot in the South Pacific inhabited by a community of some 2,000 souls, many descended from The Bounty mutineers. Stan has for many years been a man of the soil, tending his small dairy herd, hand rearing his free-range pigs and chooks. Since his marriage break up he has moved to Australia

When you talk to Stan, you talk slowly. Stan responds in carefully measured tones, each word searched for, deliberated upon, double checked to make sure it can’t be misconstrued and tasted and rolled around his mouth before eventually being uttered in an unhurried drawl.

Stan is the epitome of larghissimo.

Stan places pauses for effect throughout his prose. Stan will roll his eyes back in his head as he searches for what he wants to say. It is all that I can do not to finish his sentences for him, because that would be rude. I used to love my long conversations with Stan not that we said that much to each other. Silence wasn’t something to be feared. Silence was something to be revered. It meant that he was reflecting on what he had or wanted to say. And whatever Stan said was very important - and he only ever said it once. If Stan could say in three words what he wanted to say then why on earth would he use thirty?

Two very different people from very different environments.

This article was first publised in Eureka Street on January 27, 2010.